The Movement for Black Lives

Justin Leroy studies the history of the United States in the 19th Century, specializing in African American history. This blog post originally appeared as an article in "Teaching in 2020" - the fall 2020 issue of our online magazine, The Source.

Justin Leroy studies the history of the United States in the 19th Century, specializing in African American history. This blog post originally appeared as an article in "Teaching in 2020" - the fall 2020 issue of our online magazine, The Source.

By Justin Leroy, Ph.D., Department of History, UC Davis

Teaching the history of the present is challenging, even more so when it comes to social justice movements like the Movement for Black Lives. To help us think through the current moment, the best historical examples are the abolitionist movement to end slavery, and the black freedom struggle of the twentieth century. Both offer some constructive lessons for understanding the anger, hope, and fear many of us feel in response to the ongoing struggles against police violence and white supremacy. And teaching about what it took for both of these movements to be successful—and what they left unfinished—can help all of us feel more empowered to support the current Movement for Black Lives.

The abolitionist movement and the black freedom struggle share several features. They both took place over long periods of time; even using a narrow chronology, we can date abolitionism from about 1830 to 1865, and the black freedom struggle from about 1945 to 1968. So when we think of major movements for racial justice, we measure in decades, not weeks, months, or years. That’s important to keep in mind when we’re feeling frustrated that weeks of protests don’t result in the changes activists are demanding. It’s also a reminder that we should be thinking of the first wave of Black Lives Matter organizing in 2014 as part of a period of prolonged change that we’re still probably in the early stages of. Earlier movements for racial justice also relied on a diversity of tactics. Even though the end of slavery and civil rights were ultimately enacted through legislation, electoral strategies were only one part of a much broader struggle. Years (and years and years) of direct action and grassroots organizing created the conditions of possibility for social change that was ultimately enshrined in new laws. It’s also important to remember that abolitionists, civil rights organizers, and Black Power activists were all vilified by conservatives and liberals alike. They were called fanatics, un-American, and dangerous. They faced reactionary violence perpetrated by individuals, counter-movements, and the government itself. We all know about the Ku Klux Klan, and many of us are also familiar with COINTELPRO, the FBI’s program to counter the rise of Black Power, but there were dozens of anti-abolitionist race riots in northern cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York in the 1830s and 1840s—in other words, in places that were hostile to slavery, but who saw abolitionists as a threat because of their “radical” views. These earlier movements were also incomplete and left much undone. The end of slavery did not ensure black social and political equality, and the fall of Jim Crow did nothing to ensure black economic rights. We still live many of those consequences today.

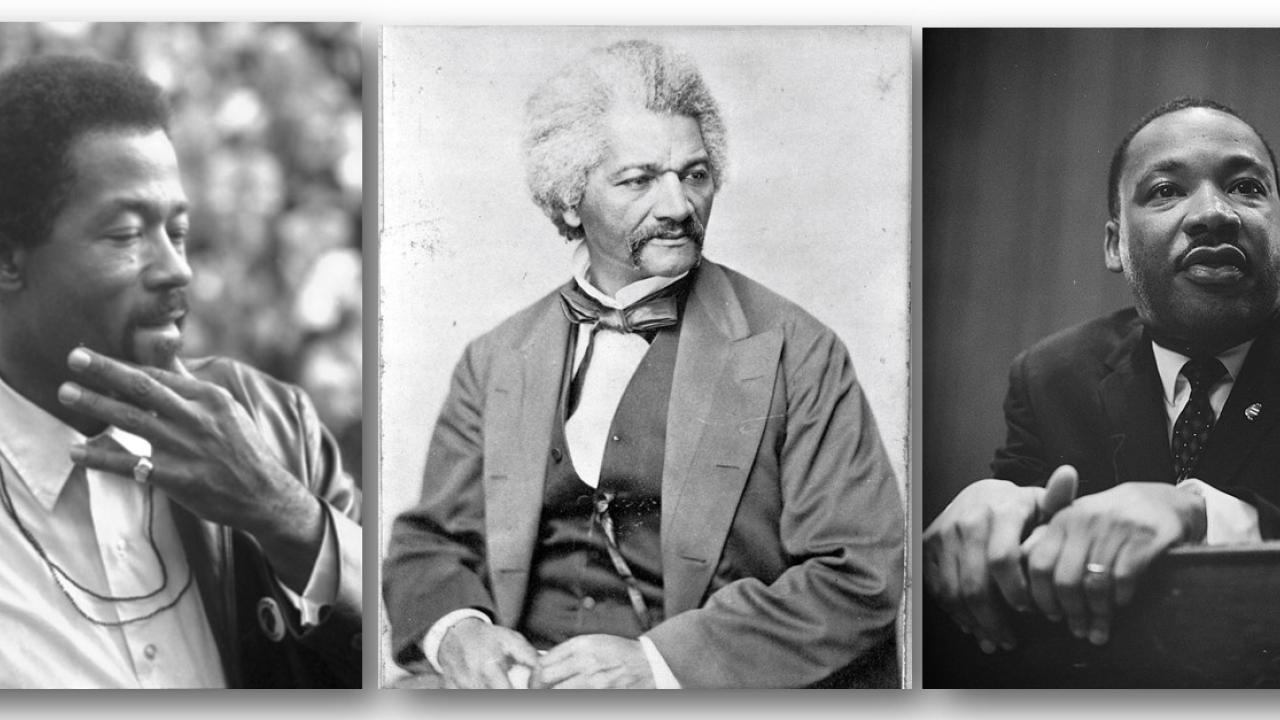

Participants in both the abolitionist movement and the black freedom struggle left behind a wealth of primary sources to study, and these sources are a reminder of how much activists of earlier generations were able to accomplish, as well as what seems to stay the same. We still read Frederick Douglass’s speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” not as a reminder of a long-distant past, but because of how resonant it still feels despite the end of slavery. The same can be said of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which he criticizes white moderates who are more devoted to order than justice. Documents like these are excellent opportunities for discussions about how we might think of the relationship between change and continuity when it comes to racial justice. One activity that I’ve fund especially productive is asking students to compare the Black Panthers’ Ten Point Program, which outlined their demands and their political philosophy, with the Movement for Black Lives’ policy platform. The latter is clearly inspired by the former, but there are also some important changes—for example, the Movement for Black Lives makes violence against black women and black queer and trans people central to their vision (and even this shift owes much to the tireless organizing of Black Panther women and black feminists that came after, such as the Combahee River Collective).

I think the best way to get students thinking about how the movements of the past relate to those of the present is with the question “how does social change happen?” There are many valid answers to that question, and by understanding our own theories of social change, we also come to understand that there is no objectively “right” or “wrong” way for Movement for Black Lives activists and their supporters to agitate for change; there are only ways that adhere to or don’t adhere to our personal theory of change. For example, if you think that reasoned persuasion of the majority is how society changes, then you’re probably not going to think that shutting down freeways and making people angry is a particularly effective strategy. If you believe that the electoral process is a sham and that both parties are agents of white supremacy, you might not think voter registration drives are the best use of your time. Then, you can have students test their theories by using the histories of earlier social movements as examples, with the goal of understanding social change as a much more complex process than it might seem.