The Power of Historical Documents to Make Sense of Crises

114 years ago, at 5:12 a.m., a catastrophe that would end up reshaping an entire cityscape, rattled awake San Franciscans. The 7.9 magnitude earthquake, and the massive fires engulfing the city that followed, decimated the city, killed thousands, and forced hundreds of thousands more people to upend their lives and relocate elsewhere. The trauma that San Franciscans experienced in April 18, 1906 was recorded in photographs, letters, reports, family stories. The trauma that Americans are experiencing now in the midst of the global pandemic is being chronicled on social media posts, in medical records, on sidewalk chalked drawings, and in news reports.

In our current moment of crisis, it’s important for us as educators to help students make sense of it. History teachers have the opportunity to highlight how people have endured and responded to crises in the past. If ever there were times to reflect on continuity and change, historical context, and historical empathy, now is when we can let the power of these historical thinking skills sink in. The CHSSP has many resources – including a brief video about an important personal artifact from San Francisco in 1906 along with a tool that can be used to analyze it – that can help students understand the significance of the earthquake. We have also created and curated collections of primary sources, lesson plans, recommended literature lists, and additional resources that can support our shared attempt at distance learning and teaching in this deeply uncertain time.

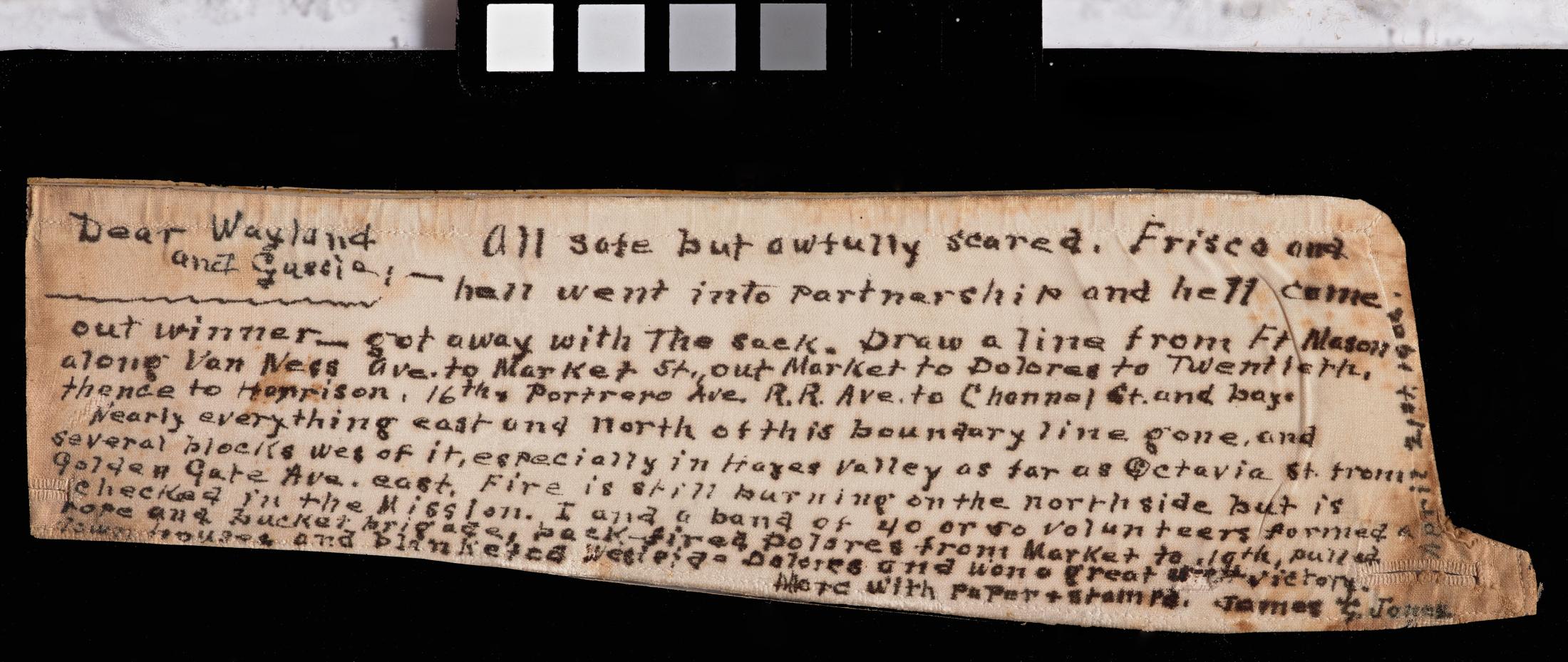

When our current crisis started to unfold, we at the CHSSP struggled to find ways to help make sense of the world for students, teachers, and now parents. A document that seemed especially relevant was a letter that archivists at the California Historical Society introduced to me a couple of years ago, as part of our shared Teaching California project. Composed on the collar of a man’s dress shirt, and mailed from San Francisco to New York City on April 21, 1906, James Graves Jones wrote to his family to tell them that he was safe, but also to inform them how badly damaged the city was. In the immediate aftermath of this environmental catastrophe, paper was hard to come by. So out of apparent desperation, Jones tore off the collar of a shirt, wrote a brief description of what was happening, and mailed it across the country to his family. This is the full text of what he sent:

| More with paper and stamps. James G. Jones

April 21st, 1906"

Taken by itself, this is an incredible example of how shattered the city of San Francisco was in the wake of these disasters. The collar vividly illustrates the lengths that families went to in order to stay in touch during emergencies; this is certainly something that Zoom-happy hour or Facetime-obsessed families can relate to. But put in the hands of California students, imagine the observations, questions, and insights that would surface from an examination of this letter and the shirt collar. When I started to construct a lesson around this document, I planned for students to “read” it in many ways, first by literally sourcing this artifact, which begins with making observations about its production and message. Then I figured that students would wrestle with questions about how and why it was created. Next, the student should view this as one piece of evidence that connects to larger questions like “How did people in the past respond to emergencies?” “Why do people move?” or “How do families remember their past?” Learning how to “read” or make sense of this source helps students to develop their own interpretations about the significance of historical items. More broadly speaking, studying documents like this connects students with their communities and the past in ways that their textbooks do not. Reading this letter alongside viewing photographs of people displaced by the 1906 earthquake and fire, for example, allows students to learn about their communities in new ways, and it also provides a way for them to construct a sense of the past that is useable for them. This month, more than ever, we can, as educators, encourage our students to find meaning in the artifacts like this from events that at one time seemed so distant, but today, take on a special meaning.