Teaching LGBTQ Topics in 2021

by Wendy Rouse and Beth Slutsky

As educators and historians, we spend a lot of time honing our craft and discussing with colleagues “the best way to teach” certain historical topics and perspectives. Of course we know that there is no one right way to approach any piece of historical content. Generally, our instructional goals are to get students to understand the complexity of the past by posing open-ended questions, having them grapple with a somewhat messy array of documents, and then asking them to form their own interpretation of that question using those documents as evidence. Doing this is an artificial construct, aimed to mimic for students the process of historical inquiry that takes years for professional researchers to do. Yet, there is value in having students learn about topics in this contrived way because it teaches them the critical thinking skills and dispositions to learn about evidence, perspective, and the power of voice and narratives. It’s here where we often get stuck: how do we organize the topics, voices, and narratives to draw students’ attention to the complexity and the larger significance of the past? How do we make it relevant to their present? These questions have particular resonance when we talk about teaching LGBTQ topics at the K-12 level.

The necessity of teaching LGBTQ history has never been more apparent than in the current political climate. Over the past year, hundreds of anti-LGBTQ laws have been proposed across the country. Several have specifically attempted to prohibit teaching about these topics. California educators remain committed to an inclusive curriculum and continue to lead the charge modeling best practices in teaching LGBTQ history.

But, the path has not always been clear. When California educators started to implement this flagship law, SB48, otherwise known as the FAIR Act, which called for an inclusion of LGBTQ Americans in U.S. history courses at the K-12 level, so many questions arose. Most of the discussion has centered around how to make our curriculum more inclusive while efficiently managing our limited instructional time.

One of the key issues has been about whether to create stand-alone or integrated lessons. Stand-alone lessons are significant because they allow students to do a deep dive into a specific topic. This can be useful when addressing big issues in the LGBTQ past. Here are a few examples of lessons that do just that:

- This 11th grade lesson about the Lavender Scare asks the question: How did the conditions of the Cold War lead to the criminalization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Americans? This is a five part lesson that frames the Lavender Scare through the experiences of federal employees who faced public interrogation about their sexuality and national security status. The lesson encourages students to think critically about LGBTQ history as a central feature of U.S. history.

- This 11th grade lesson on the Black Cat Tavern Riots considers the causes and consequences of a riot that occurred at a gay bar in Los Angeles. In response to continual police brutality, the LGBTQ community fought back against a police raid in 1967. This incident occurred two years before the Stonewall Riots in New York and highlights the longer history and broader geographical scope of LGBTQ efforts to resist discrimination.

These in-depth explorations of key events in LGBTQ history can be productive especially for teaching historical thinking skills. However, an integrated approach of learning about LGBTQ people and experiences alongside other topics is perhaps even more effective. Integration as an organizing method for courses – as opposed to stand-alone topics – means that instruction about LGBTQ individuals and topics should be layered within existing content. This strategy allows for an easier adaptation of existing lessons and a more seamless integration of new material. Integration normalizes LGBTQ individuals as a part of our past and as a part of our present. But this history has long been concealed. It is our job as educators to reverse this erasure. Highlighting key figures in LGBTQ history can help make LGBTQ history visible. However, a narrow focus on individuals (and especially propping them up as “heroes)” can also be problematic and limiting. Instead, a focus on key themes in LGBTQ history can offer more depth and meaning. Here are a few examples of how the integrative approach of teaching LGBTQ history can do just that.

- This 2nd grade lesson asks students the question: How do People Remember the Past? A number of different primary sources provide opportunities for students to learn about diverse family histories. One of the documents includes the story of an LGBTQ family.

- This 11th grade lesson about immigration at the turn of the 20th century asks students to consider “push” and “pull” factors motivating people’s decisions to leave their homelands. In addition to learning about Asian and European immigrant experiences, along with nativism, students also learn about the perspectives of people like George McBurney and Geraldine Portica, who both faced deportation because of their sexual and gender identities.

- This 11th grade lesson uses an integrated strategy and asks students to consider: How did various movements for equality build upon one another? Students explore how various groups, including the LGBTQ community, organized for equality in the post-world war era.

- This 11th grade lesson explores similar themes of resistance by posing the query: How was the war in Vietnam similar to and different from other Cold War struggles? How did the war in Vietnam affect movements for equality at home? It also take the integrative approach by considering range of perspectives, including LGBTQ individuals.

- This Ethnic Studies lesson takes an intersectional approach and asks students to explore In what ways have members of my community engaged in political activism? Sources from Bayard Rustin, Latinos Unidos, and the Black Panther Party, for example, help students learn about LGBTQ activism in an several different communities from the 1960s-1980s.

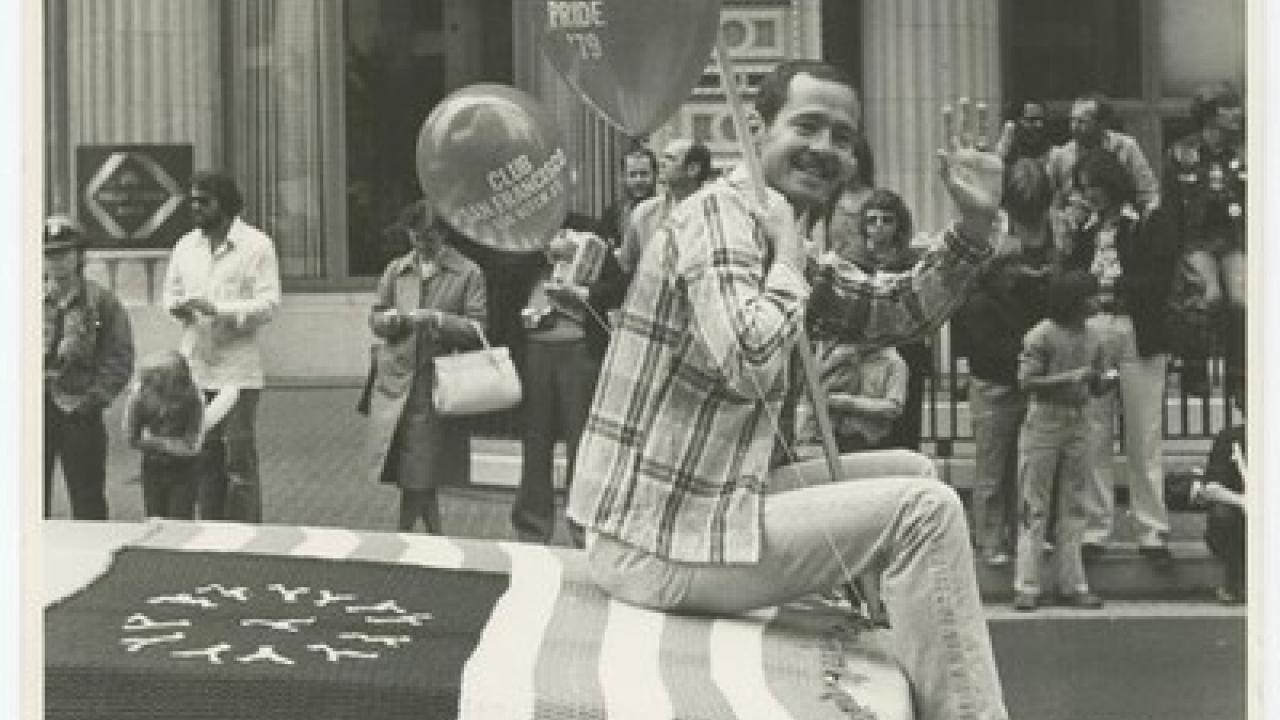

It is important to move beyond a simple story of oppression and resistance. Looking at the complexity of the past means considering the spectrum of experiences. LGBTQ people have not just survived, they have thrived. When denied rights, they formed organizations to demand equality. When faced with hostility from society, they created queer communities. When banished from families, they formed their own chosen families. We should seek to highlight the formation of LGBTQ subcultures, the resilience of LGBTQ people, and the joy and love inherent in the LGBTQ experience. These rich stories of the human experience offer our students so much more than just lessons about how people survived in the past. They offer lessons about how we can thrive in our present.

Our goal as teachers is not just to educate but also to empower our students. There is hope in our history. Sometimes we just need to shine a light on it.

The CHSSP Sites have collections of lesson plans and resources on many more topics related to LGBTQ History. For more information:

- The UCLA History-Geography Project

- The UC Berkeley History Project

- The UC Davis History Project

- The UC Irvine History Project

- The UC Santa Cruz History and Civics Project

Additional Recommended Resources and Collections:

- ONE Archives

- Our Family Coalition: Teaching LGBTQ History

- Library of Congress: LGBTQ Pride Month Resources

- Teaching Tolerance: Best Practices for Serving LGBTQ Students