Reclaiming Our Stories through Platicas & Photos

When the shelter in place order first went into effect, the UCLA History-Geography Project (UCLAHGP) considered what sort of resources were needed to support families, distance learning objectives, and historical thinking skills all at the same time. The result is the project known as Platicas, meaning informal and intimate conversations with a loved one that “allow us to witness shared memories, experiences, stories, ambiguities, and interpretations that impart us with a knowledge connected to personal, familial, and cultural history.”* Platicas encourages parents/guardians and kids to talk about their family through the lens of family photographs.

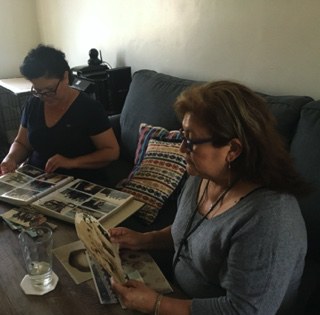

Cindy Mata, the Associate Director of the UCLAHGP, first envisioned the project while working on her graduate degree in Latin American Studies at CSULA. She sees it as a culturally responsive approach to teaching history. Last year, Mata enjoyed platicas with her mother and aunt while pouring through old family albums filled with pictures from El Salvador and California (pictured at right). As a history educator, Mata sees the value of centering students’ own history in their learning. As Mata points out: “We spend the majority of our time in school learning about other people’s history and tend to forget that we hold this wealth of knowledge in the home.”

Cindy Mata, the Associate Director of the UCLAHGP, first envisioned the project while working on her graduate degree in Latin American Studies at CSULA. She sees it as a culturally responsive approach to teaching history. Last year, Mata enjoyed platicas with her mother and aunt while pouring through old family albums filled with pictures from El Salvador and California (pictured at right). As a history educator, Mata sees the value of centering students’ own history in their learning. As Mata points out: “We spend the majority of our time in school learning about other people’s history and tend to forget that we hold this wealth of knowledge in the home.”

The Platicas project brings families together to discuss a family photo, and therefore analyze a primary source. Such a source - an original documentation of an event - helps a young person learn about his or her family’s past while also asking the sorts of questions a historian would about the photo: “What is going on in this picture?” and “What clues or evidence lead me to think this?” Students are already encouraged to ask these types of questions of a primary source in their history classrooms. Through conversation with a family member who knows something about the photo, a student can begin to better understand the family’s context in those years. Did they live somewhere else? Were there more children in the family then, or fewer? What did the people in the photo do for work and for fun, and how was any of this related to what was happening in the world at the time this photo was taken? By learning about the surrounding context for their family photo, students gain a better understanding of a particular event or person, while putting together the pieces to better understand how their family’s story fits into the events of an era.

Students gain another historical thinking skill by examining a photo, which is understanding perspective or point of view. The Platicas project asks students to consider who took the photo and for what purpose. Was it a high school graduation photo, taken by a proud parent to share with family and friends? Or did an adult snap a picture of siblings lined up on a holiday? What can we tell about the kids’ expressions that gives insight into what the adult asked of them? How was the picture posed and why might it have been posed in this way? Or, is the photo an action shot, a candid look at a loved one cooking dinner or playing in a soccer game? Why might the person holding the camera have taken the photo, and what might that tell us about the affection between these people? Understanding the photographer’s (or author’s) perspective helps students think critically about the primary source and what it can, and cannot, tell us.

At its core, the Platicas project is really about the conversation and about young people being able see their stories as part of the story of America, a key goal that is reflected in all of Mata’s work. Mata credits the influence of scholars like Dolores Delgado-Bernal and Shawn Ginwright in shaping such understandings of a history education. Included in the Platicas project are a number of recommended activities to mark student learning. A primary source investigative tool, adapted from the National Archives, guides students through examining the family photograph. Writing prompts are included, as are recommendations for recording audio/video or writing a poem. Mata developed the various pieces of this project through collaboration with her colleagues at UCLA and other ethnic studies educators. She asked elementary, middle, and high school teachers and the California History-Social Science Project network for their input.

At its core, the Platicas project is really about the conversation and about young people being able see their stories as part of the story of America, a key goal that is reflected in all of Mata’s work. Mata credits the influence of scholars like Dolores Delgado-Bernal and Shawn Ginwright in shaping such understandings of a history education. Included in the Platicas project are a number of recommended activities to mark student learning. A primary source investigative tool, adapted from the National Archives, guides students through examining the family photograph. Writing prompts are included, as are recommendations for recording audio/video or writing a poem. Mata developed the various pieces of this project through collaboration with her colleagues at UCLA and other ethnic studies educators. She asked elementary, middle, and high school teachers and the California History-Social Science Project network for their input.

In the short amount of time Platicas has been available, Mata has been thrilled to see colleagues use and adapt the project for their home or classroom. As Mata explains, it is “my sincere hope that families use this activity to engage in conversations about their personal histories, that students learn more about their families, and that family members feel a little more connected to each other.” During this time, when homes serve as classrooms, Mata sees the Platicas project as allowing students, families, and teachers to witness shared memories and “collectively reimagine what the history classroom can be and make more room to center the lived experiences, saberes (multiple ways of knowing), and histories of our students and their families.”

*Bernal, Dolores Delgado, and Cindy Fierros. “Vamos a Platicar: The Contours of Pláticas as Chicana/Latina Feminist Methodology.” Academia.edu, 2016.

**To download your own copy of UCLA's Platicas assignment, click here. We welcome your feedback; please let us know how you’ve used this resource. You can reach us at chssp@ucdavis.edu.

For more curriculum and resources from the UCLA History-Geography Project, click here.

And for more ideas, visit the CHSSP Homeschool page.