Current Events and the Environment

I am writing about the Current Context: A Focus on the Environment series, an environment-based current events classroom resource, at an exciting time. The series began in 2017, and the first eighteen issues were published during Trump’s presidency, when there was a clear disconnect between the science and observation regarding climate change and what the president and his administration prioritized. When I wrote these, I tried to balance the difficult scientific and policy-related realities with my desire to encourage students to believe that, with concerted attention to the problems, there could be real improvement. Now, we have federal leadership that takes very seriously the need to prioritize the health of the environment. The possibilities for progress at the state, national, and even international levels seem better than ever.

Regardless of who holds office, students deserve to learn more about current climate and other environmental realities. The Current Context series, sponsored by Ten Strands, has sought to provide environmental learning opportunities. This secondary classroom resource focuses on the positive developments (like electric car technology) while not ignoring the threats (like sea level rise, wildfire, and drought) or the issues related to equity (like the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color or the lack of equitable access to parks and green space). Each issue works to weave together the science, history, and policy that together provide a fuller context for understanding any given topic, while also providing maps, data, and other key sources that students can use to think critically through the issues on their own.

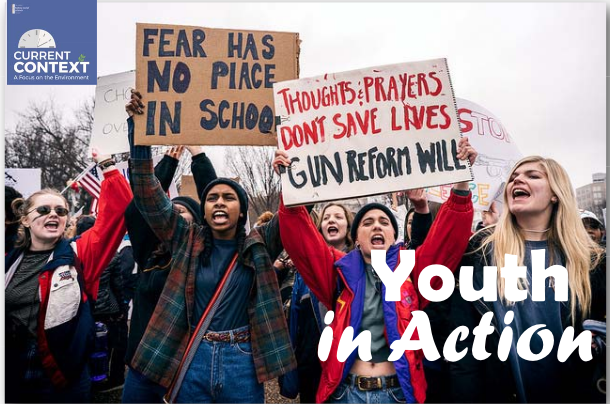

The more I speak with students, from elementary school to university, and the more I hear from teachers about their students’ concerns, the more I feel a mandate coming from our students to teach them about environmental quality, climate conditions and predictions, and the points of leverage for forward momentum. Students in California don’t appear to lack the motivation for climate action, so we as educators can serve them well by equipping students with the information they need to see clearly what is in front of them and to engage in meaningful action. Of course, youth have long been on the forefront of tackling issues of national concern, like racism, gun violence, and, of course, environmental degradation. They have stood up and committed their time and energy to influence matters they are too young to vote on but that will inevitably shape their future.

The environmental and social challenges facing us today, like air pollution and the communities that suffer the most from it, derived from a series of choices made in the past by industries, governments, society at large, and individuals and communities. So the issues aren’t new, and they’re complex. But when, say, 11th-grade students can link their history class’s study of the civil rights movement to their science class’s study of toxic chemicals, and in doing so engage with environmental justice, they will be able to think more deeply about how to unravel the complexities that need to be addressed in order for reform to happen. I recently spoke with a high school environmental science teacher who is working with government and history teachers in her school to provide activities that flesh out learning around climate change and climate justice. Students are likely to remember this sort of cross-disciplinary approach to learning, especially on an issue that is so relevant to their own lives.

Many of the Current Context resources address global issues, such as agriculture in the age of climate change, but all seek to help students see the California connection. Students can use these connections as a springboard to dive into investigations about specific conditions, opportunities, and challenges in their own communities. Other Current Context issues were written specifically with a California audience in mind, such as one on the Oroville Dam, through which one-third of L.A.’s water flows. The California History–Social Science Project’s environmental literacy webpage provides numerous classroom and teacher resources that will prompt student inquiry around environmental issues.

I look forward to writing more of these Current Context issues during President Biden’s tenure, as he leads an administration that places great value on environmental quality and does not shy away from tackling long-entrenched practices that are harmful to the Earth and its inhabitants. One clear indication of Biden’s commitment to environmental stewardship and equity is his choice of former New Mexico Representative Deb Haaland for Secretary of the Interior. Haaland, an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Laguna, is the first Indigenous American to lead the Department of the Interior.

Begun in 1849 as a government agency meant to handle the nation’s internal affairs, the Department of the Interior eventually encompassed a broad number of priorities, including the National Park Service, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and the Bureaus of Indian Education and Indian Affairs, to name a few. In the late 19th century, after devastating wars between the US military and many Native Americans, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established boarding schools for Indigenous youth, with the explicit purpose of erasing their ties to their culture and language and assimilating these young people into American society. These schools’ legacies are largely that of being places of great trauma for their students.

Of course, Indigenous culture did not disappear under this government-led assault. Secretary Haaland’s belief in the need for bold solutions to “protect the future of our communities, country, and planet” are influenced by her own and other tribal peoples’ conceptions of the land and humans’ relationship to it. Haaland’s leadership at the Department of the Interior is an indication to our youth that real change is possible. We owe that to them.

This blog was originally published on the Ten Strands website on April 13, 2021.

Lead photo by Jose Flores.

Secretary of the Interior photo: https://www.doi.gov/secretary-deb-haaland