What can schools do to improve civic engagement?

In last week’s blog post, I wrote about the new federal lawsuit charging the state of Rhode Island with preventing people from exercising their constitutional rights because the state’s educational system failed to prepare their neediest students to assume their responsibilities as citizens. Since that post went online, I’ve gotten a number of questions from teachers and school leaders who are working to develop or expand their own local programs to improve student civic engagement. In this post, I thought it might be helpful to answer just a few of these questions.

What is civic engagement?

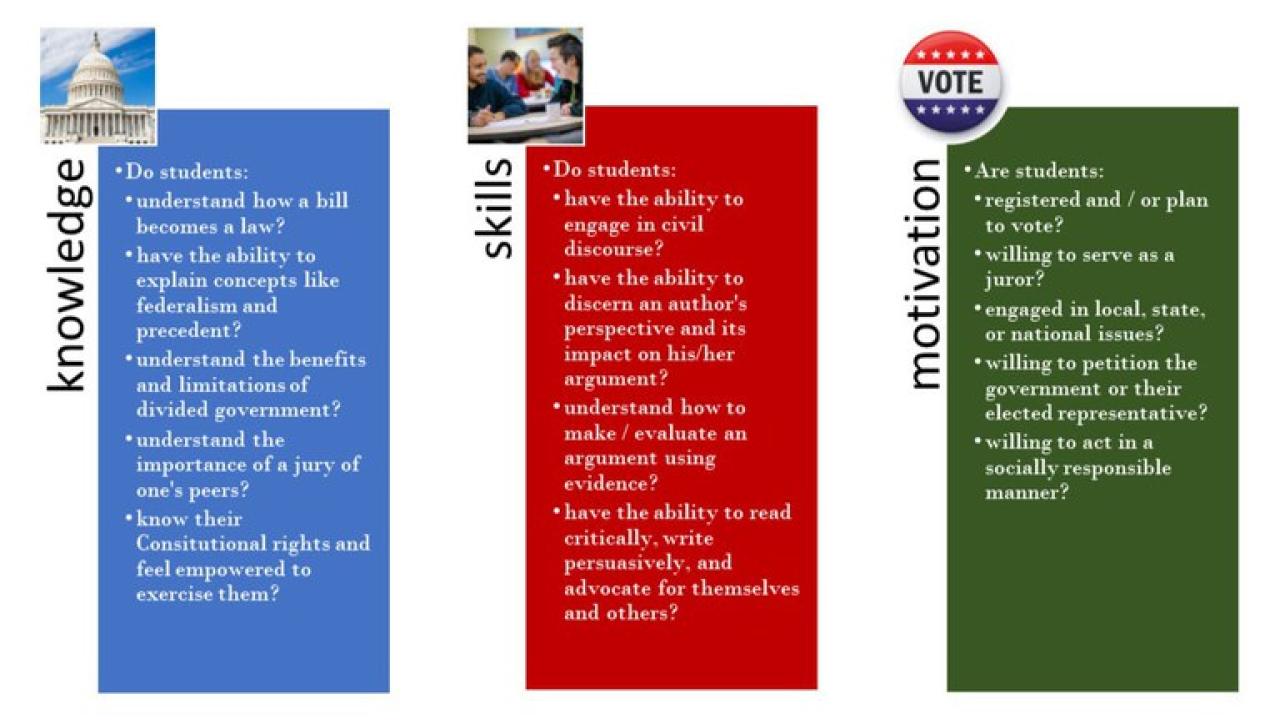

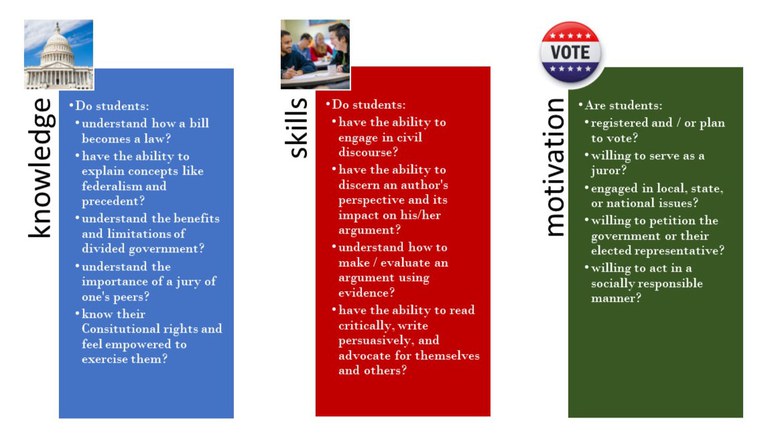

I’ve yet to find a simple and concrete definition of civic engagement that most everyone agrees upon. It is an abstract concept, often measured by admittedly subjective and vague descriptions of people willing and able to make a positive difference in their communities and beyond. Most folks do seem to agree that civic engagement is valuable, that we don’t have enough of it, and we better redouble our efforts to get it back to the level that it was (whatever and whenever that used to be). There is somewhat more consensus among researchers, who argue for three major goals for students as future citizens - that they are knowledgeable about our government and history (knowledge), that they have the abilities they’ll need to assume their roles as future citizens (skills), and that they will want to participate in the democratic process (motivation). I’ve developed the following graphic to summarize these goals –

How can we impact civic engagement?

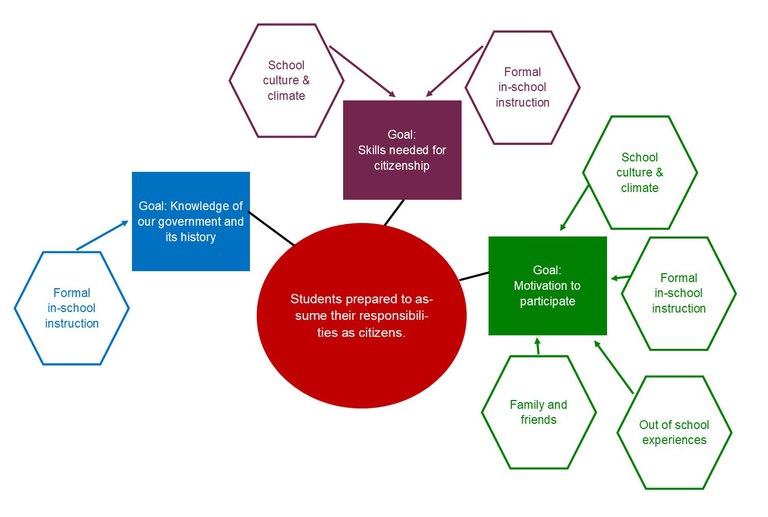

Although a student’s family and their community in which they live make a significant impact, schools can also play a big role in helping prepare young people for their civic responsibilities. In addition to classes in history and government, school culture, climate, and pedagogical strategies can all make a difference.

- Coursework can impact student content knowledge, their skills, and their motivation. Having a coherent and robust program of history-social science instruction throughout the K-12 course of study (see California’s History-Social Science Framework for an example) is likely the most important thing school districts can do. It teaches children about how our government functions now (and in the past). It develops the skills our future citizens will need to participate fully in our democratic system of governance – the ability to think critically, to use evidence in support of an argument, to advocate for their position through writing, and to engage in civil discourse. And it can also impact a student’s willingness to participate – to vote, serve on a jury, or petition the government.

- School culture and climate can impact student skills and motivation. For example, research has shown that well-crafted extracurricular activities, connected to their in-school coursework, can help students develop an interest in politics and can give them valuable experience serving their community. A school climate that encourages students to engage in civil debate and discussion, and offers students the ability to work in teams for a common goal also teaches students important skills and helps develop their willingness and ability to work with others.

- And out of school activities (such as volunteering in their community) can make a difference, most notably on a student’s willingness to participate in the political system, although the evidence of their impact on student motivation has been more difficult to document systematically than other programs or activities.

I developed the following graphic to help me summarize what the research has shown about the impact of the different activities on student civic engagement and share it here in case it also helps you:

I don’t teach government, but what can I do in my own classroom?

We’ve gotten this question from numerous teachers, especially those in the earliest grades, where students are many years away from being able to do things like vote in a presidential election. World history and economics teachers also ask questions, given the distance between their content and coursework in American government and history. My answer to both of these groups, and really all teachers, is that there are helpful things you can do to facilitate the development of not just knowledge, but also of skills and motivation. Encouraging discussion and debate in your classroom both develops student oral discourse skills and teaches the value of listening to others. Allowing students to vote on classroom rules or activities helps them understand both the value of participatory democracy and the way to behave when the vote doesn’t go their way. And encouraging your students’ participation in student government, community based organizing, or service learning introduces your students to broader roles they can play in their communities For more specific ideas, organized by grade level, return to the History-Social Science Framework for detailed suggestions and teaching ideas.

Where can I find out more?

We’ve compiled many of our civic education resources on this page. CHSSP sites across California offer a variety of programs that address student civic engagement. Many of us also work with our colleagues at the local county office of education through ongoing partnerships and collaborative efforts focused on civic education. You might also want to check out the resources listed on the Department of Education’s Civic Education page, as well as the Power of Democracy, the Constitutional Rights Foundation, the Center for Civic Education, the California Democracy School Initiative, and Mikva Challenge websites.

And if you’re looking for relevant research on the topic, the following list of studies is admittedly incomplete, but it does offer a sampling that might be of interest:

References:

Bennion, Elizabeth A, and Xander E. Laughlin. 2018. "Best Practices in Civic Education: Lessons from the Journal of Political Science Education." Journal of Political Science Education 14 (3): 287-330.

Blevins, Brooke, Karon LeCompte, and Sunny Wells. 2016. "Innovations in Civic Education: Developing Civic Agency through Action Civics." Theory and Research in Social Education 44 (3): 344-84.

Boulianne, Shelley. 2015. "Social Media Use and Participation: a Meta-Analysis of Current Research." Information, Communication and Society 18 (5): 524-38.

Callahan, Rebecca M., Chandra Muller, and Kathryn S. Schiller. 2012. "Preparing for Citizenship: Immigrant High School Students' Curriculum and Socialization." Theory and Research in Social Education 36 (2): 6-31.

Callahan, Rebecca, Kathryn Schiller, and Chandra Muller. 2014. Preparing the Next Generation for Electoral Engagement: Social Studies and the School Context. Author Manuscript, National Institutes of Health, Chicago: National Institutes of Health Public Access.

CIRCLE: The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. 2003. The Civic Mission of Schools. New York: The Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Geboers, Ellen, Femke Giejsel, Wilfried Admiraal, and Geert ten Dam. 2013. "Review of the Effects of Citizenship Education." Educational Research Review 9: 158-173.

Jaffee, Ashley Taylor. 2016. "Social Studies Pedagogy for Latino/a Newcomer Youth: Toward a Theory of Culturally and Linguistically Relevant Citizenship Education." Theory and Rsearch in Social Education 44 (2): 147-83.

Josephson, Jyl. 2018. "Teaching Community Organizing and the Practice of Democracy." Journal of Political Science Education 14 (4): 491-499.

Kahne, Joseph, Erica Hodgin, and Elyse Eidman-Aadahl. 2016. "Redesigning Civic Education for the Digital Age: Participatory Politics and the Pursuit of Democratic Engagement." Theory and Research in Social Education 44 (1): 1-35.

Wong, Alia. 2018. "The Students Suing for a Constitutional Right to Education." The Atlantic, November 28.